Welcome to The S-Curve

Now you will be able to receive the latest announcements, product updates, and our insights on the mortgage market in real time.

The name of the blog, the S-Curve, is a reflection of our logo and the central feature of our prepayment model. S-curves are seen in nature in many phenomenon, from population growth to prepayment and default models. Our first S-curve, in the early 1990s, used the arctangent function, then piece-wise linear functions, and evolved over time to be more complex and vary by FICO, loan size and LTV. This evolution encapsulates both the timeless nature of fundamental relationships and constant innovation to describe them better over time.

We hope you find the information useful and we look forward to your feedback.

-

FRED Adds AD&Co’s GSE-and-Borrower-Option-Adjusted Spreads for CRT IndicesNews

FRED Adds AD&Co’s GSE-and-Borrower-Option-Adjusted Spreads for CRT IndicesNewsAD&Co US Mortgage High Yield Indices

The Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) portal, housed by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has been publishing AD&Co’s CRT indices since 2019. These series posted under the overall name of “US Mortgage High-Yield” include total return rates and credit and option-adjusted spreads (crOAS) – a projected return’s spread over Treasury (in the past, Libor). These series are available going back to 2014-end and tiered by CRT initial supports.

Tier 0 includes all CRTs with under-25 bps support; Tier 1 bonds have supports exceeding 25 bps, but not 95 bps; Tier 2 has support from 95 bps to 175 bps; Tier 3 – from 175 bps to 375 bps, and, finally, Tier 4 – above 375 bps. The actual bond’s name (As, Ms, or Bs) that matches each tier can vary over time and between Fannie Mae’s CAS and Freddie Mac’s STACR transactions. We define Mid-Tier as the aggregation of Tiers 1 through 3. A CRT to be included in an index must have a factor of 0.25 or higher.

While actual rates of investment return are computed model-free, crOAS levels come from the AD&Co model. Importantly, the crOAS indices that date back to 2014 do not account for the GSE call option embedded in a CRT and therefore overstate the expected return. See, for example, index CROASMIDTIER for Mid-Tier or index CROASTIER0 for Tier 0; the latter currently shows crOAS of about 600 bps.

What is New?

Over the last couple of years, AD&Co developed a model to account for embedded GSE calls. Most CRTs are now issued with a five-year call and a cleanup call. Exercised in the interest of the GSEs, those options reduce investor return. Our December 2024 Quantitative Perspectives[1] laid out the theoretical foundation of our methods. A subsequent September 2025 Pipeline article[2] listed results of the production analysis across the entire CRT cash market.

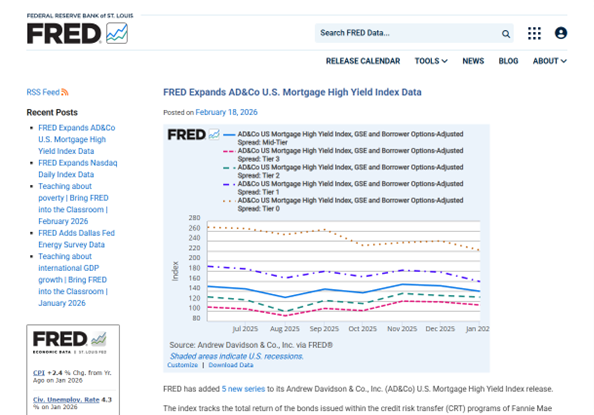

We have been using the new method in our CRT Monitor monthly publication for the last several months. We have also started sending the new series to FRED, which has adopted it with an announcement. The new crOAS series goes back only to June 30, 2025, and is reported by the same tiers as the previously computed ones. To indicate the difference in the series, the new series contains “GSE and Borrower Options-Adjusted Spread” in the names. A screenshot of FRED’s onboarding, showing all the indices together, is seen below.

Source: FRED As expected, the more protected CRTs are priced at tighter, more realistic, crOAS levels. They never reach many hundreds of basis points when the GSE option is accounted for.

[1] A. Levin and N. Salwen, Valuation of Credit Risk Transfer with Embedded Calls, Quantitative Perspectives, Dec 2024.

[2] A. Levin, Comparative Valuation of CRTs with and without Embedded GSE Calls, Pipeline 191, Sep 2025.

The S-Curve Archives

-

News

NewsAD&Co US Mortgage High Yield Indices

The Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) portal, housed by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has been publishing AD&Co’s CRT indices since 2019. These series posted under the overall name of “US Mortgage High-Yield” include total return rates and credit and option-adjusted spreads (crOAS) – a projected return’s spread over Treasury (in the past, Libor). These series are available going back to 2014-end and tiered by CRT initial supports.

-

Thoughts

ThoughtsIn July 2025, the US Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) announced that the government-sponsored entities (the Enterprises or GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, would permit lenders to choose between Classic FICO and VantageScore 4.0 credit score models for loans sold to the GSEs. FHFA also stated in a social media post that the tri-merge standard would be maintained for mortgage underwriting. Nevertheless, some mortgage industry stakeholders recommend moving away from the tri-merge standard for GSE mortgages in favor of a single or bi-merge report standard.

-

News

As housing faces more climate threats that result in more losses, the insurance program that it sits on is teetering on the brink of collapse. Yet, the home insurance market has three distinct stakeholders that have competing priorities, and today, there is no motivation for a collaborative solution.

Understanding how to strengthen and protect the current structure requires looking at the cost burdens along with the risk for each of those parties.

-

Thoughts

ThoughtsThere has been a flurry of activity in the mortgage markets since the 2018 passage of the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act. This act requires the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA, now known as US Federal Housing) to validate and modernize the credit score models used in the housing finance system. It should be noted that so far, the discourse has been around mortgages sold to the Enterprises (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). Ginnie Mae has not provided any guidance on their plans to start using new credit score models.

-

Events

EventsAndrew Davidson & Co., Inc (AD&Co) proudly sponsored IMN’s 11th Annual Mortgage Servicing Rights (MSR) Forum by Informa at the New York Hilton Midtown. Senior modeler Daniel Swanson joined the “Managing Delinquencies & Forbearance Value” panel in discussing how servicers are adapting to today’s market and the evolving delinquency trends.

-

Podcast

PodcastTune in to our fourth episode of AD&Conversations with Kevin Lin and Eknath Belbase, our product lead for our Climate model. In this episode, they discuss the new Climate Impact Suite (CIS) pilot project, and Belbase outlines several challenges the team is navigating, including:

-

Podcast

PodcastTune in to our fourth episode of AD&Conversations with Kevin Lin and Eknath Belbase, our product lead for our Climate model. In this episode, they discuss the new Climate Impact Suite (CIS) pilot project, and Belbase outlines several challenges the team is navigating, including:

-

Podcast

Andrew Davidson was invited to speak on Equifax's Market Pulse Podcast titled, "Driving Efficiency and Resilience in the Mortgage Industry" live at the 2025 MBA Annual Convention in Las Vegas.

Andy explains how variations in data files can distort risk assessment, creating a dual risk for lenders: extending credit to borrowers more likely to default while overcharging customers whose risk is overstated.

-

Thoughts

ThoughtsOur latest Policy Perspective written by Richard Cooperstein offers an analysis of the U.S. housing and mortgage finance markets, focusing on key trends and forward-looking risks. While housing markets are not fully efficient, they do respond to economic imbalances which create opportunities and vulnerabilities. This article explores how demographic shifts, credit access, interest rates, and climate risks shape both housing demand and supply.

Key findings include:

-

Podcast

PodcastJoin Kevin Lin in a conversation with Richard Cooperstein as they dive into Kinetics, AD&Co's modular platform designed to deliver the full power of our models and analytics; with the flexibility to license only the tools you need.